To co-design or not to co-design?

Co-design has recently been embraced by the water sector in Australia and overseas. But what is co-design beyond creative workshops and colourful post-it notes? And what value does it bring the water sector, if any? As part of the Water Source Expert Series, RMIT University’s Tanja Rosenqvist and Elia Hauge discuss the potential of co-design to transform the water sector for the better.

Co-design — more than buzz?

You have probably heard the term "co-design" used regularly in recent years — how could you not? It has quickly become one of those buzzwords, somehow finding its way into every meeting, report and media release. It’s a bit like "sustainability", "resilience" or "liveability" — it can mean something and not very much at the same time. As a result, the term is often generously sprinkled when a project needs a little extra pizzazz.

With all the co-design buzz, it would be easy to disregard it as a fad, or to run key staff through a two-hour training workshop and be done with it. That would be a great shame. Co-design, when done authentically, offers an opportunity to fundamentally transform the way the water sector thinks and works.

So, what is co-design?

The "co-" in co-design stands for co-operative design, although some call it collaborative design, and others suggest "co-" stands for community or conversation. Semantics aside, they all hold true. Cooperation, collaboration, community and conversation are all at the core of co-design.

To understand co-design, we need to look at its (activist) history. Co-design has its roots in Participatory Design, which emerged in Scandinavia in the 1970s. During this time, workplaces were changing dramatically with the introduction of new technologies and automated ways of working. Early Participatory Design projects sought to democratise the development of these new technologies by involving those affected by their design, workers, and their unions, in decision-making. This had the secondary benefit of ensuring their skills became a resource in the design process.

Co-design has since moved beyond the workplace and into the design of everything from smartphone apps to public policy, but democratisation, and more recently also decolonisation, of design remains its core aim. Authentic co-design, therefore, requires those affected by design to be involved in designing, and co-design typically has an explicit commitment to bringing the voice of the most resource-weak or marginalised groups into the heart of decision-making. Here, they are treated not as "users", "consumers" or "customers", but as experts — experts of their own lived experiences. In co-design, people with lived experience and those we typically consider "professionals" or "experts" come together, as equals, as co-designers.

While co-design might sound a lot like community engagement, it’s important to note that the two terms are not synonymous — far from it. In the water sector, community engagement is often performed as community consultation. This may involve one or more town hall meetings where a proposal is presented to a community for feedback, or a proposal posted on a web portal, where community members can respond through a survey or an open text field. This is not co-design. Co-design implies a much deeper promise to collective decision-making.

How is co-design done?

Co-design, done authentically, may offer the water sector a new way of thinking and working — thinking and working with rather than for community. This is a significant shift in mindset, which requires serious organisational commitment and appreciation for the core principles of co-design; sharing power, prioritising relationships, using participatory means, and building capacity (McKercher, 2020).

In co-design power is shared between co-designers: This means that those who normally have power must be willing and able to give away power. This is the hardest part of co-design. In community consultation an organisation retains decision-making authority and can use community feedback how they see fit; it can even be discarded entirely. In co-design, decision-making authority must be shared equally among co-designers, which means decisions made collectively by co-designers should not be rejected. Embracing co-design, in other words, involves moving up Arnstein’s famous ladder of participation from "Consultation" to "Delegated Power".

In co-design relationships between co-designers are prioritised: Co-designers need to build trust and mutual understanding, something rarely achieved through one-off events. Where co-design really proves useful is, therefore, in long-term endeavours where co-designers meet on multiple occasions to explore and find solutions to shared concerns. Through such ongoing collaborative processes the relationships between co-designers, and co-designers themselves, are transformed. Good co-design should be approached as a long-term learning process from which no one escapes unchanged.

Co-design uses participatory means: This allows co-designers to freely express themselves, to share and build upon each other’s ideas and to take an active role in decision-making. Slideshows and long reports do not cut it. They foster one way communication. Co-design is not about relaying information to co-designers; they must be given the opportunity to contribute in ways that they are comfortable with. This might be through the use of storytelling, visual tools, or creative mediums to access different and even tacit knowledges held by co-designers.

Co-design typically involves some level of capacity building: Here, it’s important not to equate this to building "water literacy" among co-designers. While this can be valuable, capacity building involves giving all co-designers the support needed to work and think in new ways and to learn from others. The lived experience of co-designers is as important as the expertise of water professionals. Water professionals may need to learn to listen to co-designers' lived experience and to appreciate and value their contributions.

Applying co-design in the water sector

There are many opportunities for utilising co-design in the water sector in Australia and internationally. We have already seen a range of organisations experimenting with co-design. Melbourne Water, for example, applied a co-design process when developing the Healthy Waterways Strategy for Port Phillip and the Westernport region in 2016–2018. In June 2021, Indigenous communities came together with academics and industry to co-design solutions for water contamination in Western Australia.

Internationally, the RISE (Revitalising Informal Settlements and their Environments) program, led by Monash Sustainable Development Institute, has setup an extensive program to co-design location-specific water sensitive settlement improvements in 24 informal settlements in Indonesia and Fiji.

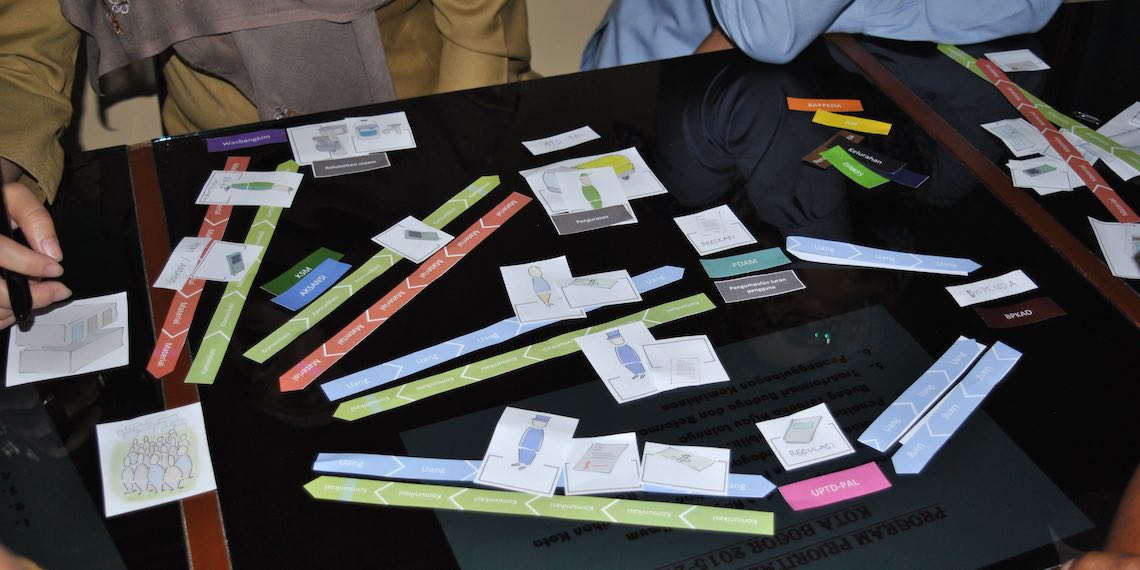

In our own work, we have used co-design to rethink the governance and management of urban sanitation services in Indonesia. We brought together members of low-income urban communities, local government, and NGO stakeholders, to reflect on current approaches and to explore alternatives. The purpose was to build relationships between co-designers and to allow them to share and discuss the challenges they experience in urban sanitation service provision.

As facilitators, we situated community knowledge and experiences front and centre to even out power imbalances. We also ensured co-designers had opportunities for informal networking to build relationships. We used the participatory tools, shown below, to support knowledge sharing and mutual decision-making, and we built capacity among co-designers in using these tools prior to co-designing.

We envision a future where co-design is used for these and many other purposes — a future in which a broad range of co-designers, from community to government, are meaningfully involved in making complex decisions about things like water security, climate adaptation, waterway health and more. We also see opportunities in embracing the heterogeneity and complexity of "community" and exploring ways to include the voice of non-human community members, like waterways and animals, in co-designing our shared water futures.

To co-design or not to co-design?

This is indeed the question! And it’s an important one. If co-design is embraced as more than one-off creative workshops and seen as a way to build partnerships and transform power relations, then the Australian water sector has much to gain.

The co-design literature points towards benefits like improved focus on customers, better public relations, higher customer satisfaction, improved creativity, reduced project failure risk, and enriched innovation practices (Steen et al., 2011). If that’s not enough, the need to support and strengthen community participation in water and sanitation management is also inscribed into Sustainable Development Goal 6.

However, co-design is not easy or quick. It requires serious long-term organisational commitment and a deep appreciation for the expertise, experience and knowledge that all co-designers bring to the process. Too often is something heralded as co-design when, in reality, it’s just community consultation with post-it notes.

So, before you jump on the co-design bandwagon and embark on your first (or next) co-design adventure, make sure you and your organisation are fully prepared, and that your efforts are authentic co-design. This handy little learning tool may help you.

Want to experiment with co-design?

We are currently exploring how co-design principles and community engagement inform climate adaptation strategies in the Australian water sector. Drawing from these principles, we are taking a collaborative approach and looking for advisors and potential research participants to be involved with the project. If this sounds interesting, don’t hesitate to reach out.

References

McKercher, K. A. (2020). Beyond Sticky Notes. Doing Co-design for real: mindsets, methods and movements. Sydney, Australia: Beyond Sticky Notes

Steen, M., Manschot, M., & De Koning, N. (2011). Benefits of co-design in service design projects. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 53-60