This Polish city is using mussels to monitor water quality

While all water professionals are aware of the delicate balance between human systems and biological indicators, the thought of relying on the mechanisms of mussels to safeguard a city’s population from polluted drinking water takes trust in nature to new heights.

The Dębiec Water Treatment Plant in Poznań, Poland, employs the natural intelligence of mussels as sensors for water quality changes in the Warta River, the city’s primary surface water supply.

With a low tolerance for pollutants, mussels are well known for clamping their shells shut when water quality is poor. And the treatment plant has devised a hybrid sensory system by combining the pollution-detecting prowess of mussels with computer technology.

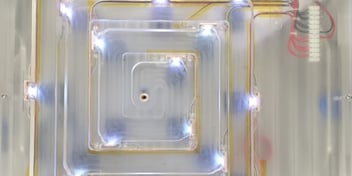

Eight mussels with sensors glued to their shells work with a network of computers. If the water is clean, the mussels stay open; if the water becomes polluted, they close, signalling to the sensors that water quality is low.

It’s a handy mechanism for a notoriously polluted waterbody; the Warta River flows through some of the densest population areas in Poland, and some of the country’s oldest industrial zones.

Engineers at the Dębiec Water Treatment Plant are alerted to water quality issues by the mussels, whose sensors work in conjunction with a computer system that monitors parameters tracked via artificial sensors.

And while the system has been designed to take into account possible changes in the mussels behaviour, if four mussels close simultaneously, the system shuts down automatically.

According to ZMEScience, the AquaNES project — supported by the European Union with the aim of integrating nature-based elements into water management systems — has been researching indicator organisms.

“Using an organism as an indicator (bioindicator) cannot be accidental. It requires extensive field research that aims to accurately characterise natural occurrence conditions,” writes AquaNES.

“The best indicator organisms are those that have specific life requirements, i.e. they have a narrow ecological (occurrence) scale. This means that a number of different factors will limit their vital functions or even eliminate them from the environment.”

The hard-working mussels have been celebrated in the documentary film, Gruba Kaśka, directed by Julia Pełka, which explores the use of biological indicators to service human systems.

“By making this film I wanted to show man’s dependence on nature. I thought it was brilliant that humans are using mussels to create a warning system against danger,” Pełka said.

“They use the clams’ senses to protect themselves from the dangers of modern civilisation. You could say that people use them as protection from themselves.”