Paying heed to the world’s sanitation waste

More than half of the world’s population lacks access to safe sanitation. An Australian researcher wants us all to pay attention to the unpleasant business of human waste.

Dr Jacqueline Thomas, a humanitarian engineer at University of Sydney, says that 14 billion litres of untreated wastewater is produced each day in developing countries, but we don't know where it all goes.

Thomas recently published an article on the status of sanitation in developing countries that makes for alarming reading.

She explains that in developing countries, each person produces, on average, six litres of toilet wastewater each day. Some 4.2 billion people live without safe treatment or containment of this wastewater, which directly contributes to increased diarrhoeal diseases, such as cholera, typhoid fever and rotavirus. Diseases such as these are responsible for 297,000 deaths per year of children under five years old — that’s 800 children every day.

Thomas told Water Source that in the water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) sector access, to clean drinking water has been an easier concept to sell, meaning that there is less attention or conversations about sanitation.

“This is slowly starting to change. The WaSH sector realises that poor sanitation contaminates drinking water and any health gains in water supply are limited by ongoing sanitation problems,” she said.

“Sanitation problems are complex and costly. Sustainable solutions take very large investments over long periods of time. This is sometimes unfavourable to funders, who are looking for high impact projects in shorter spaces of time. More risk needs to be accepted to find sanitation solutions that work.”

Thomas noted that the issue is starting to see more NGO funding, with The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation investing heavily in innovative sanitation solutions.

"The highest rates of diarrhoea-attributable child deaths are experienced by the poorest communities in countries including Afghanistan, India, and the Democratic Republic of Congo," she said.

In spite of this growing and global problem, Thomas said that sanitation practitioners still don’t know where exactly all the human excreta flows or leaches to, due to absent or unreliable data.

It’s also contributing to environmental problems, with an estimated 80% of wastewater from developed and developing countries flowing untreated into environments around the world.

Indigenous communities not immune

The sanitation issue is far closer to home than many realise, with housing infrastructure in Australian Indigenous communities an ongoing problem.

“An assessment of 200,000 households by Health Habitat found that only 59% of households had a working toilet. The absence of a functioning toilet would increase the risks of hygiene related illnesses such as diarrhoea,” Thomas said.

“Maintenance and desludging of septic tanks is also an ongoing problem, especially for remote communities that are not connected to sewerage systems.”

Thomas notes that there have been few published studies that look directly at the impacts of untreated wastewater in Australia’s Indigenous communities.

“To fill this gap, site sanitary risk inspections would need to be carried out to assess if untreated wastewater was contaminating any drinking water sources or water bodies used for bathing,” she said.

Helping our neighbours

Thomas said that a lack of sanitation is also a serious problem for our Pacific Islander neighbours — and there’s plenty that the water community can do to help.

“There exists a large skill-set of sanitary engineers within Northern Australian water utilities. Staff from these utilities could assist with training, knowledge sharing and mentoring staff from water utilities in the Pacific Islands. This would enable water utilities in the Pacific Islands to improve operational outcomes for their wastewater treatment plants,” she said.

Another important capacity building aspect is training plumbers in the Pacific Islands in the construction of on-site sanitation systems to international standards. A common example seen with septic tank construction is there are a lot of incentives to build “non-standard” septic tanks that are much cheaper.

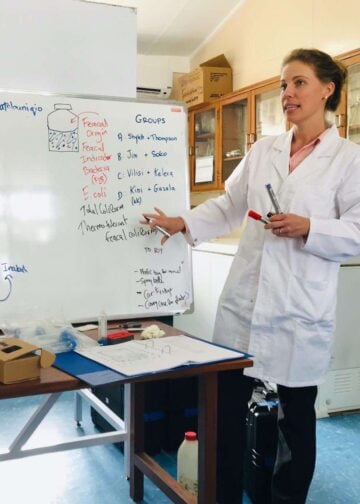

Thomas has recently been conducting research in rural Fiji, where she has seen reduced septic tank sizes and the use of alternative materials — old plastic water tanks — to save space and money in material costs.

These don’t allow for adequate containment or treatment. Instead, excreta can leach freely into the surrounding environment.

“Enhanced policies and regulations are also needed in the Pacific Islands to improve sanitation. The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade could play a role by investing in policy reviews and supplying appropriate consultants from the Australian sector who could assist in sound policy and regulatory developments,” she said.

Looking to the future

Thomas is calling for the co-ordinated investment in sustainable sanitation solutions from all stakeholders, especially governments, international organisations and the private sector. This is essential to both protect the health of our own species and all other living things.

“There needs to be more funds for sanitation implementation. Donors and private sector investors need to take risks and invest in long-term integrated projects. Integration at all levels is needed to achieve an enabling environment where there are the right policies and regulations to support both public and private sector sanitation initiatives,” she said.

"There is growing political will and community awareness in part motivated by Sustainable Development Goal 6 of Clean Water and Sanitation.

"To increate successful sanitation implementation, the needs of the community must be thoroughly considered in any project design. Further, there needs to be sound monitoring, evaluation and reporting, so that lessons learned about both success and failure, can be shared widely," she said.