Cholera crisis underscores importance of climate-resilient WASH

The extent and gravity of recent cholera outbreaks across more than 24 countries has placed the world on high alert, with the World Health Organisation raising the global crisis to a grade three emergency – the highest grade in the system.

The cholera crisis has put a spotlight back on the urgent need to ensure access to safe water for all – as stipulated by Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG6) – but it also highlights the importance of working towards climate-resilient WASH, with outbreaks in many countries worsened by the impacts of climate change.

In acknowledgement of World Health Day (7 April), Water Source spoke with WaterAid Australia Health Technical Lead Bernice Sarpong about why it’s more important than ever to ensure that WASH-related initiatives are developed through a climate lens.

“It is important to consider WASH through a climate lens because water is a cross-cutting resource integral to many sectors, including health, agriculture and the environment,” Sarpong said.

“When we look at SDG6, it's clear to see that access to WASH is linked very closely with many of the other SDGs. Pretty much all of the SDGs have an element of WASH required in order to be successful.”

Unfortunately, this also means that a lack of access to WASH has a detrimental impact across all of the SDGs, and across all of the sectors to which water is connected, Sarpong said, with climate extremes making the issue much worse.

“We know that climate change affects the water cycle, and water is critical to WASH. Some of the statistics show that by 2025, almost 66% of the world’s population will be living in water-stressed areas. That will have a significant impact on access to WASH,” she said.

“WHO has also warned that climate change is making millions of people sick, or much more vulnerable to diseases. We are seeing this occur across the world – it's a global issue. And extreme weather events disproportionately affect poor and marginalised communities.

“Considering WASH through a climate lens is absolutely critical if we are to think about public and population health as a whole and move the dial on SDG6.”

Growing crisis

Cholera is a disease caused by bacteria that infects the intestine after people consume contaminated water or food, causing severe diarrhea and sometimes vomiting, which in turn causes extreme dehydration.

Sarpong said the disease can result in death within hours if people are not diagnosed quickly and treated early enough.

“There are about 24 countries that are recording cases, including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Burundi, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Haiti, the Philippines, and many more,” she said.

“The current global cholera outbreak really is the perfect storm of climate change, conflict and financial crisis, along with human displacement.

“The disease was eradicated in a lot of countries. But we now have a significant number of countries that are going through a protracted crisis. In that sense, this global crisis is unprecedented.”

Sarpong said the latest data update from the WHO indicated that about 74,000 cholera causes and close to 800 deaths have been officially recorded as of December 2022, but it’s likely those figures are much higher in reality.

“Part of the discrepancy between the figures and the data that we are seeing is because sometimes cases are not being recorded due to limitations in surveillance systems within the country, but also due to the fear of potential impact on trade and tourism,” she said.

If someone is infected in a context where overcrowding is prevalent, it’s very easy for the disease to spread, Sarpong said: “This includes refugee camps, which is why conflict and military crises also have a part to play in disease outbreaks”.

“If wastewater with cholera bacteria somehow contaminates drinking water, which can happen quite easily in some scenarios, the disease spreads like wildfire. It is a highly infectious disease,” she said.

Water woes

While political instability, conflict and displacement all create scenarios that engender and exacerbate disease outbreaks, Saropong said climate extremes and natural disasters are playing an increasing role.

“The extremes of climate change, whether it's more droughts or more floods, tips the balance on how water is able to be managed in many places,” she said.

“Mozambique has had years of drought, which reduces access to safe drinking water for many communities. People have been forced to use unsafe drinking water. But floods can also spread the bacteria very easily.

“Stresses placed on water resource management during floods make it much easier for it to spread. Flooding creates a scenario where cross-contamination between water sources and waste can occur very easily.”

Furthermore, extreme weather events – like cyclones and typhoons – can completely devastate water and wastewater infrastructure.

“While these scenarios increase the risk of people coming into contact with a whole assortment of pathogens, the cholera bacteria is extremely virulent. Once it starts spreading, it is very difficult to mitigate,” Sarpong said.

“The world is more globally connected now than ever before. And the spread of highly contagious diseases can now occur much more easily than ever before, as well. The recent pandemic is the perfect example of this: a disease that was endemic to China became pandemic very, very quickly.”

Working with climate

Sarpong said working towards climate-resilient WASH development is now more important than ever, and starts with understanding the need for an interconnected approach to solutions.

“WaterAid’s climate-resilient WASH framework includes three key focus areas: community, the environment and institutional arrangements. And these areas are all closely related,” she said.

“We need to learn from the community to inform what will be helpful to their environment. The communities we are talking about here include First Nations and Indigenous communities, those people living with and interacting in the environment every day.”

Sarpong said it’s also important to understand the health of the catchment area in question, by using climate data and modelling to understand any patterns and changes occurring.

“Integrating this ecosystem data with government leadership at the institutional level is important for creating regulations and policies for how we engage in the environment,” she said.

“Financing and community empowerment are also crucial. Empowering the community helps to keep governance structures accountable for looking after the environment. Part of this is recognising that gender inclusion is really important, too.

“Creating a more climate-resilient WASH program is about understanding the interconnection between these three factors. But it's also about recognising that this is a multi-sectoral approach. Across all the different levels of communities, including institutional arrangements, we all have a part to play in creating a more climate resilient approach and practice.”

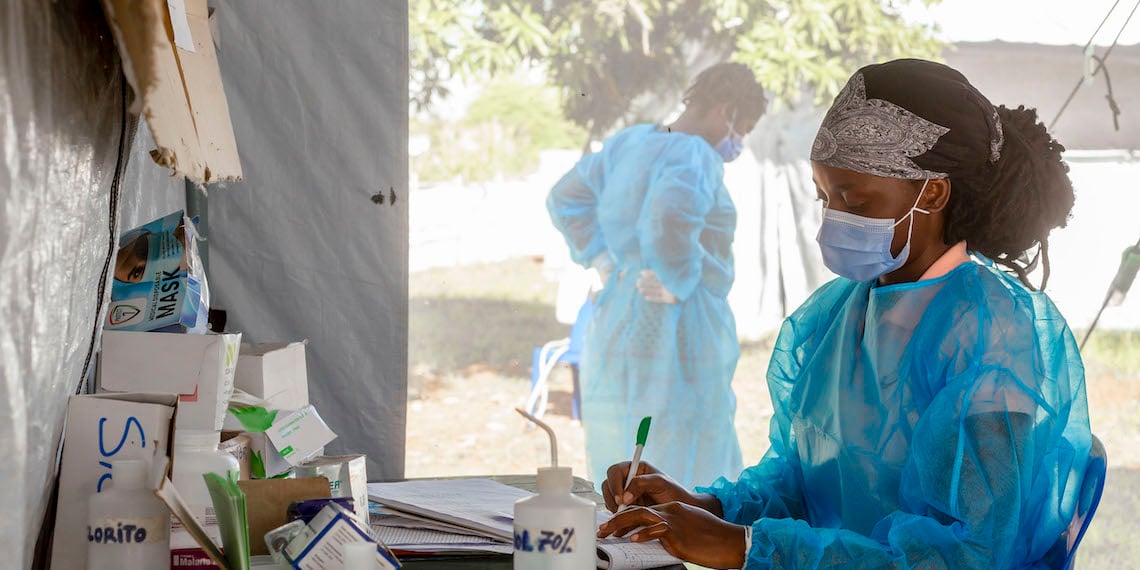

Image: Medical staff working at the Mechanhelas District health centre, treating cholera patients, Niassa, Mozambique, March 2023 (credit: WaterAid/Edson Artur at Signus)